Why do humans play games?

How do you answer when lay people ask for advice about gaming addiction or games designers want to know how to structure their product? What you need to know is how games differ from everyday life – but the boundaries are becoming increasingly blurred. Nowadays, complex online games such as “Eve” leave the rules open and more or less reflect the full complexity of our everyday lives.

However, there is one essential difference. It is highlighted by Systems Theory and has been empirically proven in a scientific study. The result is highly significant, albeit only partially tangible, because it relates to the notion of time. Let us therefore employ a metaphor: in order to play, gamers switch off the “clock in their head”. This means that, without awareness of time, the conditions are altered so that they are once again neurobiologically recognisable and valid. Or, to put it another way: gamers reformat interesting new files and adapt them to suit their existing hardware.

Firstly, this finding confirms what the biologist and constructivist Humberto R. Maturana has already said about play: A form where “it simply is what it is” – a behaviour that precedes the development of time awareness. However, this does not explain why this motivation persists into old age and, equally, there is no identifiable relationship between this naive behaviour and what Brian Sutton-Smith describes: an increase in development, converse and dialectic principle.

This gap in understanding can be filled by the theory of temporalized systems. This is a further development of biological constructivism, as proposed by Maturana. It is concerned, in particular, with how time constructs expand the scope for evolution. Its Expectations tool was used for this study. This tool dissects the technique with which humans navigate this new dimension, thanks to their extraordinary neurobiological flexibility, the attribute that has made us very successful as a species.

Nevertheless, one key problem remains: an individual can “think” time but cannot “feel” time. This inability has given rise to an independent system of time-related information. We now depend on two different systems: we need the first one for our biological existence, the other provides us with an awareness of the “meaning of life”. However, if we look at it closely, the time system turns the sequence of our original system regulation on its head. On a biological level, our experiences provide us with a feel for what is real but in the temporalized system, we first of all accept a reality and then have the experience. We have to accommodate this imbalance every day of our lives and it saps our energy and can lead us to no longer trust our own judgement.

The theory is that we play all through our lives to free ourselves from the consequences of the time system.

Systems organize the solution to a problem. For biological systems the problem is to maintain life. Maturana’s concept of “structural drift” can be likened to a drifting boat, which has to stay in balance to stay afloat. It drifts wherever this is most easily accomplished. Every resolved anxiety or difficulty is rewarded with a sense of satisfaction. This reward is generated most reliably and quickly by repeating tried and tested patterns. Time plays no role in this. The right place is exactly where we find ourselves and what we “intuitively” repeat.

The time system is concerned with improving life. We are motivated by the hope of finding a safe haven. “Gut feelings” are no longer valid because the present starting point doesn’t count. The associated feeling is permanent anxiety because it is down to us to set the course, develop strategies and change the well-established system. Now our heads constantly need information about co-ordinates and reference values. Controlling this desired state, the need to decide what to do, when and how to do it, creates the “clock in our head”.

When two systems with different values coincide, the system that uses time “wins”, because it creates irrefutable facts. Physics developed the second law of thermodynamics to explain this. Loss of energy and chaos then ensue in the “loser” system.

We don’t notice this as long as our course is predetermined and is relatively unassailable. Anxiety, depression and burnout are very rare in closed, hierarchical or religious communities. For, if we never change the reference values on the time axis, they always appear to be tried and tested, and so repeatable. The two system circuits can coincide – hope and satisfaction can be joint motivators. Games are then “meaningless” and, if they are, then they are simple.

However, the more independently we determine our course, the more often we encounter quite different reference values during the course of our navigation. We therefore no longer kill each other – we sidestep each other and form a network. This forces us to develop tactics and diplomacy. Expectations show how the room for manoeuvre on the time axis forces us to fabricate possible realities. The Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler was quite right when he said: “We are always playing.”

In everyday life we do not have the choice, especially since it happens to us unawares. In this situation, actions are mostly associated with negative emotions, because they are only proven later on – if ever. This undermines our confidence and takes up a lot of time and energy. The more open and sensitive people are to possibilities, the more crippling the effect of expectations can be and this can lead to defensive behaviour.

For the purposes of the study, these expectations were compared with those of a conscious game. The results show that, in a conscious game, expectations are massively restricted. This means that the time axis also collapses and closes down the scope of biological system regulation for indirect and therefore valid echoes of self-perception.

Such actual states can also be achieved via meditation or taking drugs. The special thing about a game is the increase in self-efficacy due to the combination with active doing. Even Sutton-Smith stresses that this is why gamers have a preference for current and unresolved themes. Accordingly, the game would be a fusion of the desired state and the actual state – a model of the harbour transformed to the conditions in the boat. And so the game transforms an expectation of possible reality into a real possibility. The advantage: anxieties can be resolved without interrupting our course.

This closed system regulation then gives rise to a number of motivating factors:

· Gamers are restored to thermodynamic equilibrium. They no longer expend energy because the energy transformation cycle is once again closed. (Zeroth law of thermodynamics)

· Desired states are repeatable and allow contextual changes in the dialectic principle. Then even one’s head finds what it is looking for: variation from the known order. Satisfaction and hope – the reward mechanisms of both systems – can combine.

· Negative emotions are transformed into positive ones. The principle behind every joke: if expectations are taken out of context and turned upside down, stress is discharged into its opposite – in a game, this is the fun of playing.

· It has been empirically proven that positive departures from expectations result in a particularly large amount of the reward hormone dopamine being released.

And so, one answer to the problem of gaming addiction comes from the conscious game itself: more fun in the unconscious game! Because the more confidence you have in dealing with your expectations, the more room there is for self-efficacy, with a lasting echo into your environment. And, in order to achieve this, the conditions and boundaries have to be clearly defined. Essentially, experienced gamers are even better at this. Because the second finding of the study also shows that only they can clearly distinguish between the two types of game.

Even in a game, it is hope that is the last thing to die – but it can be resurrected. In this way, gamers maintain balance and continuity of system processes, especially if they engage with uncertainty. Ultimately, it is always Evolution that is the true winner, because it receives stimulation for its most important resource: ideas.

Empirical study:

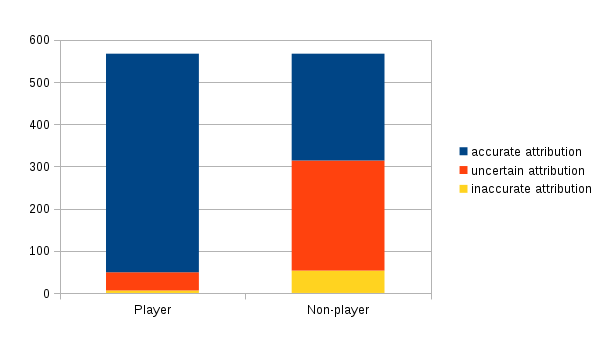

A study-group of players and a comparison-group of non-players made associations of statements with regard to their suitability for play or for non-play.

Based on the ideas of systems theory by Niklas Luhmann the statements were constructed to demonstrate either connectivity with time-systems or detachment.

Examples:

“I try to be careful and concientious so that everyone profits from it in the end.“-

„I don´t care how others cope with my decisions.“

„Even if some things repeat themselves: duties are just part of life.“ –

„Repeating myself is fun, because I have the chance to improve.“

„It relaxes me to know every now and again how late it is.“ –

In moments like this I forget time more than in others.“

A total of 567 associated statements were generated.

Associations study-group (player):

|

accurate

|

uncertain

|

inaccurate

|

|

518 91,3 %

|

43 7,6 %

|

6 1,1%

|

Associations comparison-group (non-player):

|

accurate

|

uncertain

|

inaccurate

|

|

253 44,6 %

|

261 46%

|

53 9,3 %

|

These data indicates a high significance of χ2 = 284,5 (p < .001 = 10,83)

Conclusion: Players do not affiliate with time-systems. A common attribute to distinguish play and non-play is given.

Obviously players possess more competence to estimate attitudes in the reality of play and non-play.

Dissertation – Chemnitz University of Technology – Institute for Media Communication